CFG and others have called for an 'Essentials Guarantee' to be introduced. What is it, why is it needed and what difference could it make to charities and the people they serve? Lily Bristow, Policy Intern at CFG, explains.

Before the Spring Budget, CFG and the Civil Society Group, made several asks of the government to support the Charity Sector economically. This included the call for an ‘Essentials Guarantee’, a policy proposal which ‘would embed in our social security system the widely supported principle that, at a minimum, Universal Credit should protect people from going without essentials’.1

Alongside Joseph Rowntree Foundation and The Trussell Trust, CFG is advocating for this Essentials Guarantee to support those most vulnerable in society.

During the past decade, the combined hardships created by a shift to Universal Credit, the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis have exerted massive pressures on our social security net, and ultimately, it has fallen to charities to fill the gap.

The Essentials Guarantee would help alleviate poverty in the UK and allow charities to have the greatest impact possible where they are really needed.

Universal Credit

As of November 2023, there are around 6.2 million people in the UK who receive Universal Credit (UC)2. The all-in-one benefits system, which brings together multiple means-tested benefits and tax credits into a unified payment, aims to simplify welfare and encourage ‘work and personal responsibility’3.

Since its conception, more than a decade ago, UC’s central philosophy has been to get people into ‘any job’, an ideal questioned by claimants and campaigners for lacking a ‘grasp on the realities of job hunting.’4

Labour recently promised as part of its upcoming election drive ‘if you can work there will be no option of a life on benefits’5. This shows that, even today, the notion of ‘deserving and undeserving poor’ is still ingrained across the main political parties and is therefore shaping our welfare state.

However, as the charity sector knows all too well, getting work is not simply a question of will, and the rollout of UC has been plagued with difficulty. Charities have played a vital role in filling the gaps left by extensive wait times, complicated systems and lack of guidance and support.

The Trussell Trust, having monitored the UC rollout over the years, found that in 2018, 63% of claimants were offered no help, while the most likely form of help offered was a food bank voucher.6

‘I have been waiting four weeks for one payment of benefit for food – without the foodbank I would literally starve.’7

Academic research has also consistently found that ‘an increase in the prevalence of Universal Credit is associated with more food parcel distribution’ and that there are ‘systemic and persistent problems with this new system.’8

Furthermore, evidence from more than 50,000 people shows that UC has been linked to increased psychological distress but not to increased employment.9

The transition to UC has left many claimants vulnerable and without the safety net that the welfare system is supposed to provide, leaving people in crisis, and overstretched charities supporting them through it.

Cost of living crisis

The ubiquitous problem of the sharp rise in the cost of living since 2021 has been felt across the country. The Joseph Rowntree foundation reports that in 2023 ‘7.3 million low-income households went without essentials in the first half of 2023, and 4.5 million were in arrears’ and ‘over 2 million households were borrowing money to pay their bills.’10

One example of the impact of compounding and ongoing nature of the current crisis is that during Covid-19, working tax credit as part of UC was increased by £20 a week. This was done in recognition of the extreme impact the pandemic was having on both the economy and people’s incomes.

However, the same urgency has not been extended to the cost of living crisis and people are not able to bounce back in the same way, if they ever did.

“That’s nearly a week’s worth of shopping, I know it sounds daft just to miss out on the £87 a month, but I’m struggling because £87 a month could go towards my shopping, could go towards fuel, could go towards my gas and my electric, could go towards anything.”11

Citizens’ Advice claims that they helped over 155,000 people with referrals to food banks and other charitable support in 2022- ‘up by 54% on the same time last year, and 126% higher than the year before.’12

Essentials Guarantee

CFG and the Civil Society Group are highlighting that since 5 in 6 people in low-income households receiving Universal Credit are going without essentials13, the government needs to make urgent changes to welfare in the UK.

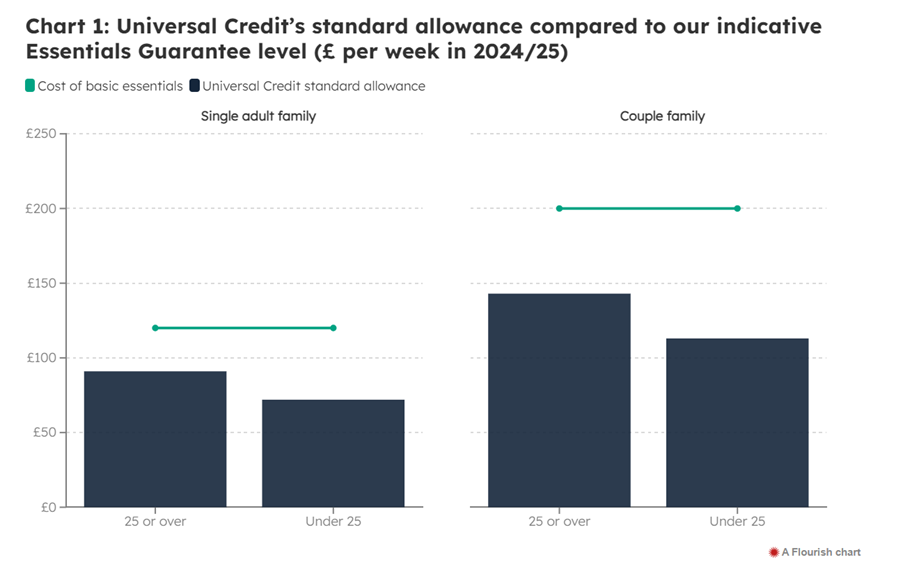

Current estimates suggest that the Essentials Guarantee should be a minimum of £120 a week for single adults and £200 for couples.’14

However, the basic rate of UC as of April 2024, is £91/week for an adult15 meaning that people are struggling to survive.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2024

The policy would introduce a legal minimum of UC, where deductions, such as debt repayments, don’t fall below the guaranteed support level. Alongside this reform, it is recommended that an independent monitoring of the cost of essentials, such as utilities and food, to update the guarantee as the cost of living evolves.

Additionally, total deductions from the Standard Allowance of Universal Credit should be capped at 15%, lowered from 25%, and deductions to repay debt to central government should be capped at 5% of the Standard Allowance.16

This simple change, which reflects the world we live in and takes account of the practical needs of the population, would benefit nine million families. While it would cost an estimated £19 billion to implement, the savings made to the overall economy, as public services are better able to cope with demand, would be greatly improved.17

Addressing the struggles of those going without food and life’s essentials should be a central priority of any government, not only in striving towards SDG 1 and 2 (no poverty and zero hunger), and Human Rights (Article 2 ICESCR), but as a popular reform.

More than two thirds (72%) of the public support an essentials guarantee, and with an upcoming election, this is a policy proposal that needs to be taken seriously.

More about the campaign for an Essentials Guarantee can be found through the Trussell Trust and Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Read CFG's news release 'Charities seek greater certainty ahead of the Spring Budget', 30 January 2024.

Article references

Bulman, M., 2022. ‘I can’t just take any job’: Universal credit claimants express anger at DWP ‘get any job now’ policy. [Online]

Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/universal-credit-job-dwp-benefit-uk-b2002220.html

[Accessed 13 March 2024].

CFG, 2024. Charities seek greater certainty ahead of Spring Budget. [Online]

Available at: https://cfg.org.uk/news/charity_sector_civil_society_group_asks_government_for_greater_certainty_ahead_of_spring_budget

[Accessed 13 March 2024].

Citizens' Advice, 2022. Citizen's Advice: Uprating Dashboard. [Online]

Available at: https://public.flourish.studio/story/1707826/

[Accessed 27 March 2024].

Citizens Advice, 2024. What Universal Credit is. [Online]

Available at: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/benefits/universal-credit/before-you-apply/what-universal-credit-is/

[Accessed 13 March 2024].

Clark, D., 2024. Number of people on universal credit in Great Britain from May 2023 to November 2023. [Online]

Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107124/uk-number-of-people-on-universal-credit/

[Accessed 13 March 2024].

HM Treasury, 2010. Spending Review 2010, London: The Stationary Office.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2022. Findings - From pandemic to cost of living crisis: low-income families in challenging times, s.l.: s.n.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2023. Cost of Living. [Online]

Available at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/cost-of-living

[Accessed 27 March 2024].

Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2024. Guarantee our Essentials: reforming Universal Credit to ensure we can all afford the essentials in hard times. [Online]

Available at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/social-security/guarantee-our-essentials-reforming-universal-credit-to-ensure-we-can-all-afford-the

[Accessed 27 March 2024].

Mahase, E., 2020. Universal credit linked to psychological distress but not employment. BMJ : British Medical Journal (Online), Volume 368.

Politics.co.uk, 2024. Young people to have ‘no option of life on benefits’ under Labour government. [Online]

Available at: https://www.politics.co.uk/news/2024/03/04/young-people-to-have-no-option-of-life-on-benefits-under-labour-government/

[Accessed 13 March 2024].

Reeves, A. & Loopstra, R., 2021. The Continuing Effects of Welfare Reform on Food Bank Use in the UK: The Roll-Out of Universal Credit.. Journal of Social Policy, 50(4), p. 788–808.

The Trussell Trust;, 2018. Left Behind: Is Universal Credit Truly Universal?, s.l.: s.n.

The Trussell Trust, 2018. Universal Credit and Foodbank Use. [Online]

Available at: https://www.trusselltrust.org/what-we-do/research-advocacy/universal-credit-and-foodbank-use/

[Accessed 27 March 2024].

The Trussell Trust, 2024. Guarantee Our Essentials. [Online]

Available at: https://www.trusselltrust.org/get-involved/campaigns/guarantee-our-essentials/

[Accessed 27 March 2024].